Ukrainians in Europe: life between integration and the call of home

In 2022, millions of Ukrainians fled west to safety, finding new homes and a new life in the European Union. The experience also threw up new challenges

Did you know that a Ukrainian can almost always spot another Ukrainian in a crowd?

Spanning the European and Slavic worlds, so physically we could be either, meaning we don’t look noticeably different from others. Yet, with an uncanny ability, we can usually detect one another from across a room or restaurant. Call it a Ukraidar.

These days, in Europe, there are more to spot. The other day, I was sat in a café overlooking a European landmark, the Berlin TV Tower, when I heard my native language being spoken at not one but three different tables.

It did not surprise me and I did not give it much thought. Berlin has long been diverse and multicultural. Yet the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 changed millions of lives.

During the first year of the war, the world was interested in what was happening. Articles were written, news channels covered events, commentators considered the options, and newspapers reported on developments. At dinner parties across Europe, it cropped up in conversation, and everyone had a view.

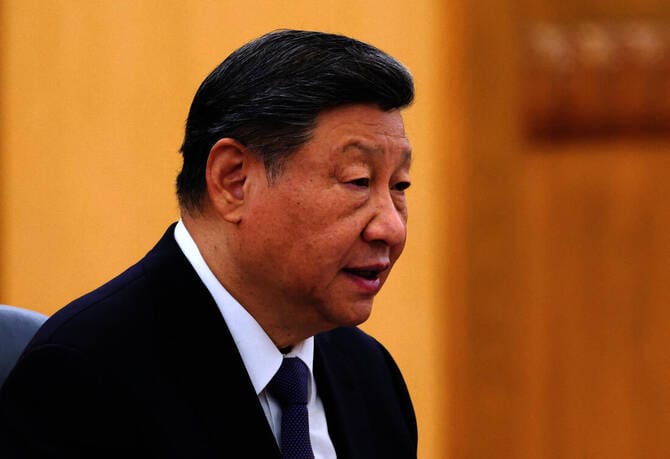

Today, two and a half years after Vladimir Putin pressed ‘go’ on his military ambitions, the war in Ukraine gets far less attention in Europe, where some are even unaware that it is still ongoing.

Braving the unknown

For the millions of Ukrainians who stayed behind in their homeland, the nightmare we all hoped would be short-lived has become a daily reality. But what of the millions who fled and moved to the safety of a foreign country?

With neither foreign languages nor often the experience of travelling abroad, many simply took their children and pets and left for the unknown, with no idea what awaited them. Foreign lands have foreign laws, foreign people, and foreign ways that Ukrainians would have to learn fast.

Before the war, the European Union had been a popular destination for those Ukrainians who could travel, either for tourism, business, education, or work. Today, I see our fellow countrymen quickly integrating into all areas of public life.

I often encounter Ukrainians in hospitality, healthcare, IT, construction, and even in government institutions in Germany. It makes me smile to see how professionally they do their jobs and how attentive they are to the problems of others.

Their communication with colleagues in still imperfect, but with increasing confidence they are learning and speaking German, despite their lifelong familiarisation with the Cyrillic alphabet.

Language matters

Once, many Ukrainians spoke Russian, especially in the country’s east, although when a Ukrainian speaks Russian, their manner of speech is different, as is their vocabulary.

This first began to change in 2014, when huge numbers dropped it for Ukrainian after Russia first invaded. Language has long been a sensitive issue in Ukraine and this remains so for Ukrainians living abroad.

As a Russian-speaking Ukrainian from the eastern Donbas region, I can confirm that it is not easy to switch from speaking only Russian to only Ukrainian, but today there is the choice.

There was no choice for my parents’ generation. The influence of the Soviet Union on Ukraine, particularly in Donetsk and other nearby regions, was so great as to practically dictate—among many other things—what people spoke.

Today, I see how younger people consciously embrace the Ukrainian language, using it more often not only in public life but also in personal interactions, yet it is not easy to change lifelong habits, especially for older generations.

Adaptation and dialogue

Ukrainians who came to Europe seeking refuge seem to have quickly adapted to the laws here. European values, in many ways, resonate with us and even serve as a model for Ukraine to follow.

Of course, there will be times where Russians and Ukrainians come face-to-face with one another in Europe. I have had this happen several times and have had both negative and positive experiences in such interactions.

Although it can be difficult, I believe it is important to try to build a constructive dialogue, to understand what motivates the person in front of you.

If someone is aggressive, or supports the views of the aggressor country (in Europe, this can lead to serious consequences, up to and including deportation), or if they maintain a neutral stance (an approach often adopted by older people), it might be worth trying to offer them information that they may not have received.

This is because Russians living in Europe still watch Russian TV, socialise with other Russians, and live in a bubble of nostalgia, with positive memories of a country they left long ago and about which they now know very little.

Of course, even the best-informed people may take different views or hold different values, yet I still believe that you need to take the time to understand the person in front of you, including why they live where they do and how they feel about where you come from. Hating someone without knowing them gets us nowhere.

Communication is key. Giving people the facts that challenge Russian propaganda and engaging through dialogue and openness rather than hostility and hatred can be much more productive for the future—for Ukraine, Russia, and Europe.

Thinking of the future

Will Ukrainian refugees return home? It is something we think about often, but it is a clearly a difficult question to answer. For now, Ukrainians can work and earn a living in the European Union, where they can live in safety.

Yet many Ukrainians’ hearts long for home. Despite being surrounded by the beauty of Italy, the elegance of France, or the grandeur of England, it is home that brings us joy, in common with so many other peoples of the world.

I feel that one day, many of us will return, but some will continue to live in their new country, while others will want to live between the two.

The Ukrainians who do go back will take with them their new knowledge, ideas, experiences, friends, and vision for the future of their country. In short, they will take the best of Europe back to Ukraine.

We want Ukraine to be a developed, high-tech nation with a strong educational system, quality healthcare, a robust social system, and, of course, one that is free and independent.

In many of these areas, Ukraine was making progress before 2022. After the war finally ends, whenever that may be, the Ukrainians who return will want to see that continue. Indeed, they will insist on it.