The cost of Lebanon’s sectarianism may be Lebanon

A failed state in many ways, Lebanon’s solution is still a mirage because its informal system of governance has no flexibility or alternatives built in. Sectarianism’s worst effects are all that is left.

To many, Lebanon is now a failed state that can trace its downward spiral back to the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in 2005.

Ever since, Lebanese institutions have grown less fit for purpose, war both internal and external has engulfed the country, the economy has tanked, Beirut’s port has been decimated, and its politics have ground to a halt from division and distrust.

In the ruins of the Lebanese state, the law of the jungle now applies, where the strongest have the final say.

Today, the strongest is the Iran-backed party Hezbollah, whose armed wing outguns the Lebanese armed forces.

Hezbollah has support (from home and abroad), a healthy weapons stockpile, plenty of money, lots of recent military experience, an established social structure, and a clearly defined system of governance. In short, it is both organized and armed.

A patchwork quilt

Lebanon’s structure should have subordinated the group, but its failures are manifold. Indeed, in many ways it has been failing since its establishment

For 400 years Lebanon came under Ottoman rule, before passing to France for a generation after World War I, then gaining independence in the 1940s.

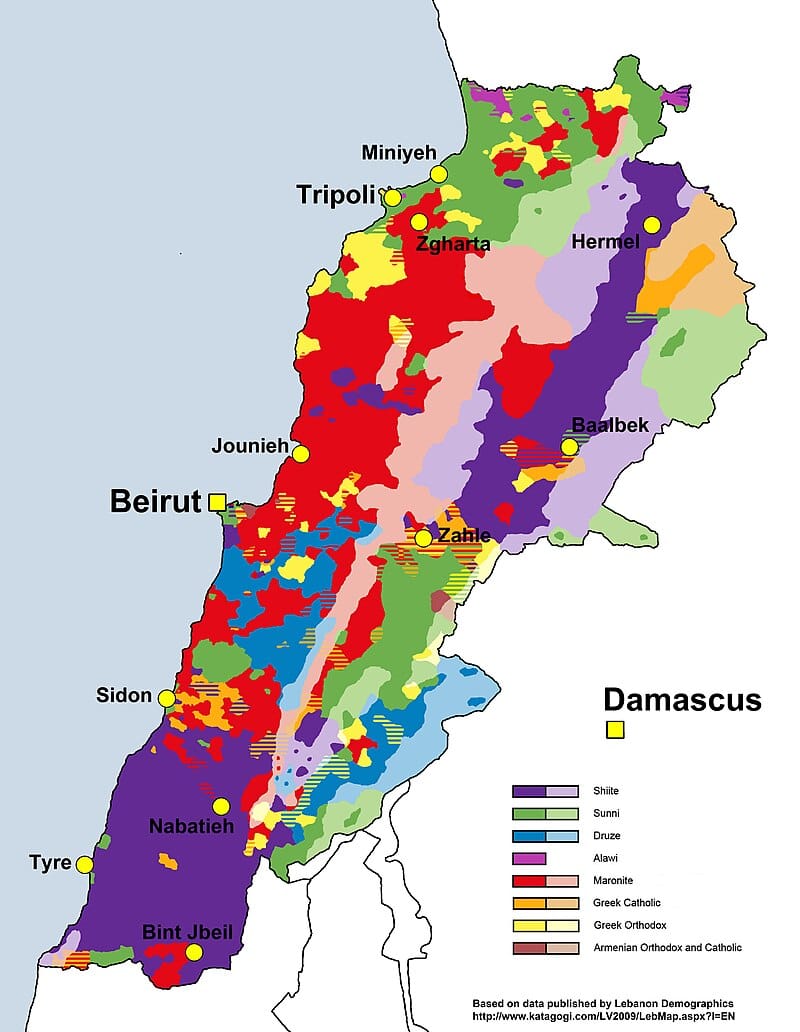

Most countries have majorities and minorities, but few are as crammed with diversity as Lebanon, which is only about two-thirds of the size of Connecticut.

The Lebanese are descended from many different peoples, many of whom invaded, occupied, and settled in Lebanon, making it a mosaic of closely interrelated cultures.

The biggest groups are Shiite Muslims and Sunni Muslims, followed by three Christian groups: The Maronites, the Melkites, and the Greek Orthodox.

Lebanon’s Druze minority comprise 4.5% of the population and each group tends to live in their own population centers.

The ‘national pact’

2 / 3

The governance of Lebanon, as either the Ottomans or the French could confirm, relies on the authorities upholding a form of social contract based on the sectarian affiliation of each of its constituent parts.

The Ottomans, for instance, introduced the Millet System, which allowed religious groups to rule themselves according to their own religious laws. This limited the Ottoman Empire’s interaction with religious minorities to the religious leader.

Of course, there was a form of a ‘republic’ in the Western sense of the word, with a constitution, parliament, council of ministers, president, army, and judiciary.

But there was also an unwritten and more important ‘national pact’ between Maronite Christians and Sunni Muslims prior to independence, a sort of equivalent or parallel constitution running alongside the official one.

This unwritten national pact uses the ideology of consensus among the various sects in Lebanon as a tool of government.

It also distributes seats in parliament and posts in government between the sects, while giving precedence to Maronite Christians, who rely on Muslims not to let Lebanon get drawn into Islamic integration.

No Plan B

For Michel Chiha, a Lebanese politician and one of the ‘fathers’ of the constitution, the country was run by a club of leaders drawn from elites from all the sects.

He felt that this club would continue to dominate the country and, as a result, resolve all its issues within the framework of dialogue and consensus.

The problem is that the make-up of the country is now very different from what it was when the system was set up. Back then, Christians slightly outnumbered Muslims. These days, Muslims comprise more than two thirds of the population.

Chiha did not foresee his cozy arrangement being replaced by decision-makers from outside these elite circles. Since he did not consider that the set-up would fail, the Lebanese Constitution lacks any clauses that provide for conflict resolution outside these strictures. In short, it lacks a Plan B.

As such, every time Lebanon confronted a crisis, the consequence was either civil war or the intervention of outside forces. Soon, the border began to resemble Nasser’s ‘tent of nations’. Lebanon was fast becoming a free-for-all.

Left with a void

Since Hariri was killed in 2005, Lebanon has had long periods without a president or prime minister. There have been numerous ‘caretaker governments’, including at present. Politicians say they cannot conduct elections due to sectarian strife.

The past 20 years have shown that there is no legislation or constitutional provision that can address Lebanon’s political or economic paralysis.

3 / 3

Despite this, any call to revise and update the constitution is met with hostility and allegations of changing the nature of Lebanon, which is built on consensus. Most Lebanese still believe in the ‘national pact’ system of distribution.

The failure of Lebanon, which is hosting more than a million refugees, is not necessarily down to its willingness to involve all the main sects, but a reluctance to adapt its systems to fit the situation.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah will continue to veto the appointment of a president, who in recent years has been a Christian.

Having slid a long way down the spiral, Lebanon may not yet have reached the bottom.