Personal reflections: The Libya I know is a land of opportunity

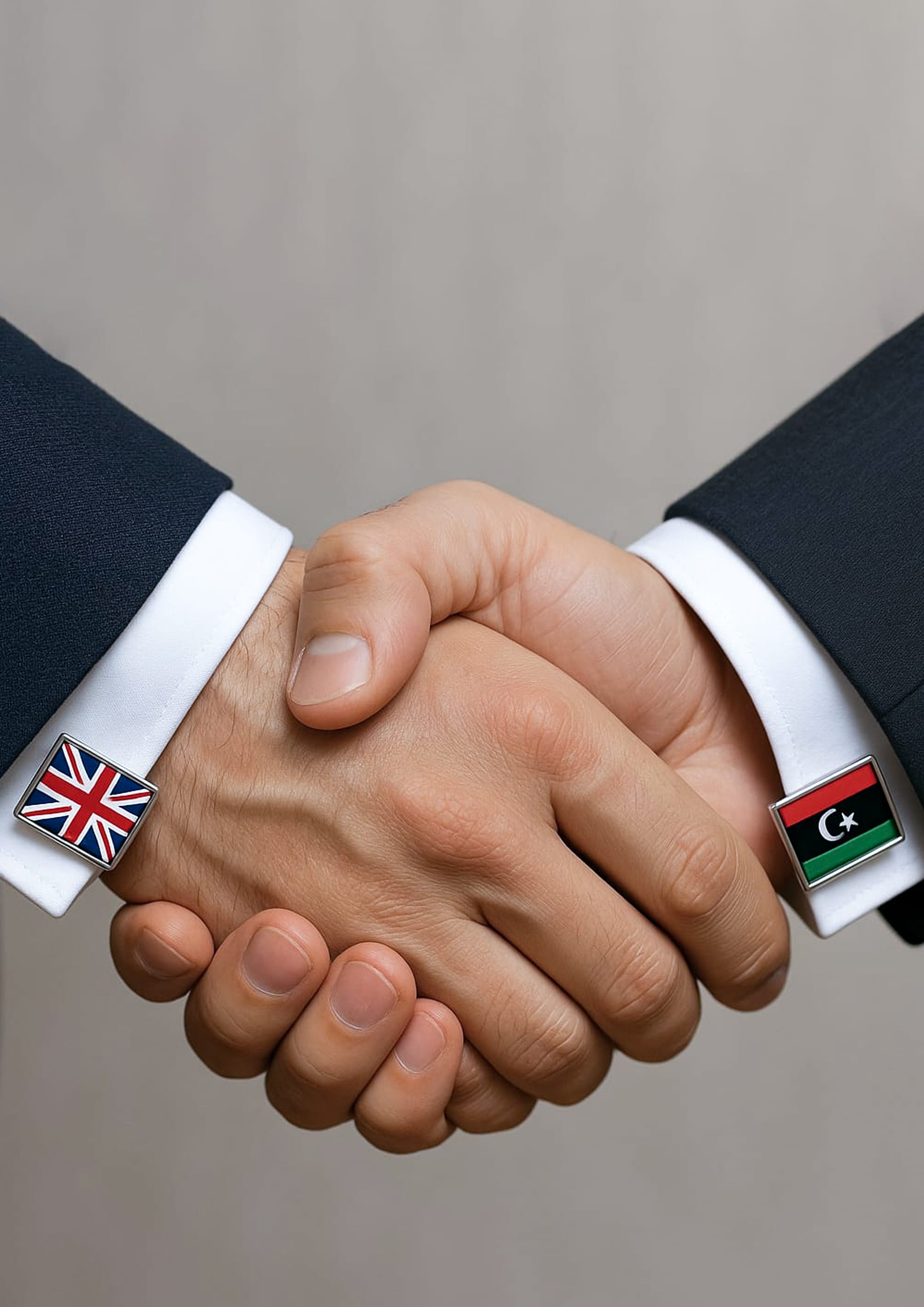

After years of stagnation, there is a yearning for change and for trade. With a stabilising security situation, reducing insurance risks, and financial mechanisms in place, UK-Libya business ties could bloom.

My connection to Libya goes back to 1977, when members of my family were sent by the Polish Communist government to work in Tripoli. My uncle was employed by Poland’s largest state-run agricultural machinery manufacturer and was seconded there as part of a broader strategy by Communist regimes to curry favour with the Arab world. It was common at the time for engineers and specialists to be deployed across the region to support large-scale infrastructure projects.

When I later served as an in the British Parliament, I was the only Member to have been born under a Communist regime—an Orwellian system in which food was scarce, everything was rationed, and people queued for hours for basic necessities, while Party elites went to private shops stocked with imported Western goods, which they paid for in US dollars.

My uncle and aunt would send us crates of Libyan oranges, fruit we had never seen before in Poland. I brought them to school, made marmalade from the peel, sketched them in our exercise books, and studied maps to find out more about Libya. To us, it was a place of unimaginable abundance, a Garden of Eden. It left a lasting impression on me and sparked a lifelong affection for Libya and its people.

The Gaddafi years

When I became an MP in 2005, I established the Libya Friendship Group in the House of Commons and led two parliamentary delegations to Tripoli during the Gaddafi era. I opposed the then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s policy of bringing Gaddafi ‘in from the cold’. I felt this rapprochement failed to resolve longstanding grievances between our nations, rooted in decades of repression, state-sponsored terrorism, and diplomatic hostility.

One of my most significant efforts was bringing the family of PC Yvonne Fletcher (the police officer murdered by a Libyan diplomat during a peaceful demonstration outside the Libyan People’s Bureau in St James’s Square in 1984) to meet then Foreign Secretary David Miliband.

Sadly, justice was never served—her killer was never identified nor brought back to Britain to stand trial. In frustration, I wrote Seeking Gaddafi, published in February 2010, exactly one year before the Libyan revolution that would finally oust him from power (and, ultimately, lead to his death).

The book documented the West’s unresolved concerns about the regime, including the Lockerbie bombing—the worst terrorist attack on British soil since the Second World War—and Gaddafi’s support for the IRA, including his provision of Semtex explosives which they used to terrorise Britain in the 1980s.

All change in Libya

I was leading a parliamentary delegation in Tunis in January 2011 when signs of unrest began. Just four days after we left, Ben Ali fled the country, and the Arab Spring swept the region.

Britain chose to intervene in Libya, and successfully: Gaddafi’s outdated Soviet-supplied tanks and radar systems were quickly dismantled from the air. Then Prime Minister David Cameron was welcomed as a hero in Benghazi, the city Gaddafi’s convoys had been on their way to attack. But there had been a lack of meaningful post-intervention planning, so the UK withdrew just as swiftly as it had arrived.

Libya soon descended into a brutal civil war, leaving countless cities devastated and many lives lost. Anglo-Libyan relations have needed a boost ever since, which partly explains the establishment of the Anglo-Libyan Business Association (ALBA), whose inaugural event will be held later this month.

It will signal a new era in bilateral relations, driven by the younger generation of British Libyans. The easing of travel restrictions, particularly in the East, has boosted confidence among investors and corporations. US President Donald Trump’s travel ban, announced in early June, notably includes Libya. The effects of this on UK-Libya relations are yet to be seen.

Moving forward

The country is torn between East and West, the latter being governed from the capital, Tripoli. Interestingly, ALBA’s chief operating officer (Suhaib Adam) hails from Benghazi, while its chief financial officer (Hesham Karim) hails from Tripoli. This dual representation helps ensure commercial unity, avoid regional exclusion, and promotes economic collaboration across Libya.

Pull Quote: The Anglo-Libyan Business Association (ALBA) will signal a new era in bilateral relations, driven by the younger generation of British Libyans

The mission is to revitalise UK–Libya trade in a way that remains authentic to the Libyan people and forward-thinking for the UK. The method is to facilitate high-level engagement between Libyan and British stakeholders through practical, industry-led workshops and strategic dialogue.

As the House of Lords debates the potential use of £4bn in frozen Libyan assets (some of which could be directed towards IRA victims), Libyan business leaders would like to speak to Parliamentarians to give their perspective and offer ideas.

Long regarded as Libya’s intellectual and cultural capital, Benghazi is undergoing rapid economic change. The Reconstruction Fund of Libya has driven major development projects, such as the new Benghazi Stadium and the Hawari Hospital. In Britain, there has been a failure to recognise this newly improved security landscape, particularly in the East.

Opportunities arise

There is a strong appetite for global commerce in Libya. Civil war and instability led to uncertainty and caution in the past, but this is giving way to confidence and capability. As security improves, investor confidence grows. For example, Weatherford Oil Services, a major US firm, recently resumed operations in Libya.

Western engagement is both feasible and necessary. After a decade of instability, a decisive shift is now underway. No longer a forgotten nation, Libya is one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that Libya’s economy will grow by 13.5% in 2025 (the world’s third fastest).

This underscores Libya’s untapped economic potential, which ALBA hopes to help unlock. Deals in Libya increasingly rely on structured contract agreements, which promote transparency and accountability for all parties. A new business culture is beginning to take hold, with a corresponding drop in insurance risk for British firms.

The Libyan people are eager to work with British businesses, but until recently this was hindered by travel bans and financial restrictions, forcing many UK firms to broker deals outside Britain. Yet the UK has the financial instruments in place to facilitate transactions from Libya, and these developments will be central to our forthcoming event.

Libya is at a turning point. Years of stagnation have produced a powerful hunger for change. This is an opportune moment for the UK to strengthen direct bilateral ties. Through ALBA, we aim to do just that, helping to reframe Libya not as a risk but as a rising partner for investment, partnership, and progress.

__

By: Daniel Kawczynski

*Daniel Kawczynski is chairman of ALBA. He was an MP from 2005 to 2024, chairing the All-Party Group for Saudi Arabia and the All-Party Group for Libya. In 2010, he published his book Seeking Gaddafi: Libya, the West, and the Arab Spring.

*