Loyalty through indoctrination: Iranian interference in Lebanese education

Religious schools are nothing new, but when it comes to the Shi’ite community in Lebanon, they represent an opportunity for Tehran to hone the next generation, regardless of the country’s constitution.

Over recent decades, a parallel education system has emerged in Lebanon, specifically within the country’s Shi’ite community, which has its roots in Iran.

To fully understand this, education must be seen not simply as learning, but as a comprehensive process that includes social institutions such as schools, institutes, and places of worship, organised in accordance with educational policies, curricula, and programmes. This system influences behaviour, builds values, and shapes attitudes, whether through teaching or through other school activities.

Before the Iranian revolution in 1979, Lebanese Shi’ites were educated differently. During the Ottoman Empire, education was primarily religious. The Ottomans employed the millet system, in which minorities were granted a degree of self-governance.

This allowed for religious communities to run their own schools, which continued through the mandate period and the establishment of the state of Greater Lebanon in 1920. The scope of official education expanded, along with the recognition of the rights of religious sects to establish their own schools within the framework of the freedom of education guaranteed by the constitution.

Shifts in schooling

In the 1940s, during the era of Lebanon’s independence, the country’s education underwent several changes, partly structural and geographical, owing somewhat to the demographic distribution of Shi’ites in Lebanon. The civil war (1975-90) prompted the emergence of school networks such as those run by associations and institutions affiliated with the ‘Shi’ite duo’: the Amal Movement and Hezbollah.

Understandably, religious Shi’ite schools were concentrated in areas where the Shi’ite community was most represented—in the south, the Bekaa, and the mountains. These areas also had ‘kuttabs,’ or schools of Islamic learning, which enjoyed a temporary boom, and could often come to dominate the educational landscape in Shi’ite villages and towns.

These were accompanied by the emergence of foreign mission schools which expanded their activities in various regions, particularly those with a Shi’ite presence. This paralleled the continued demand for schools with an Islamic character, which some families preferred over other educational institutions, because these Islamic schools were known to educate on social traditions in a cultural context.

Pull Quote: The civil war prompted the emergence of school networks run by associations and institutions affiliated with the Amal Movement and Hezbollah

For this purpose, associations were established, as in 1938 with the Al-Amiliya Islamic Charitable Society. Schools were soon opening to educate the youth of Jabal Amel displaced from the south. The contributions of Shi’ite expatriates were essential to their success.

A question of values

The emergence of modern Shi’ite schools marked a pivotal moment in modern Lebanese education. Alongside the Amiliya schools, which spread from Beirut to other regions and witnessed significant prosperity, there was also the Ja’fariyya school in Tyre and the Al-Huda schools of Habib Al Ibrahim.

In terms of official school grants, Shi’ites had a significant share. This manifested in results, with Shi’ite children’s illiteracy rates plummeting as a consequence (in 1932, the illiteracy rate among Shi’ites had been 83% according to the census). Public schools also expanded, providing primary schools to various regions, particularly Shi’ite residential areas in the south, the Bekaa, and Mount-Lebanon.

The high percentage of Shi’ites participating in public education two decades after independence indicates that they embraced the values embedded in the Lebanese educational system, particularly citizenship and its principles, which emphasise a sense of national identity, values of diversity, a culture of freedom, and coexistence. Private schools also witnessed a distinct Shi’ite boom, with continued support from expatriates, yet the quality of education varied.

The Lebanese civil war led to significant changes that affected Shi’ites and their political, social, and educational choices, with partisan schools emerging, notably those established by Hezbollah, Sayyed Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah, and the Amal Movement.

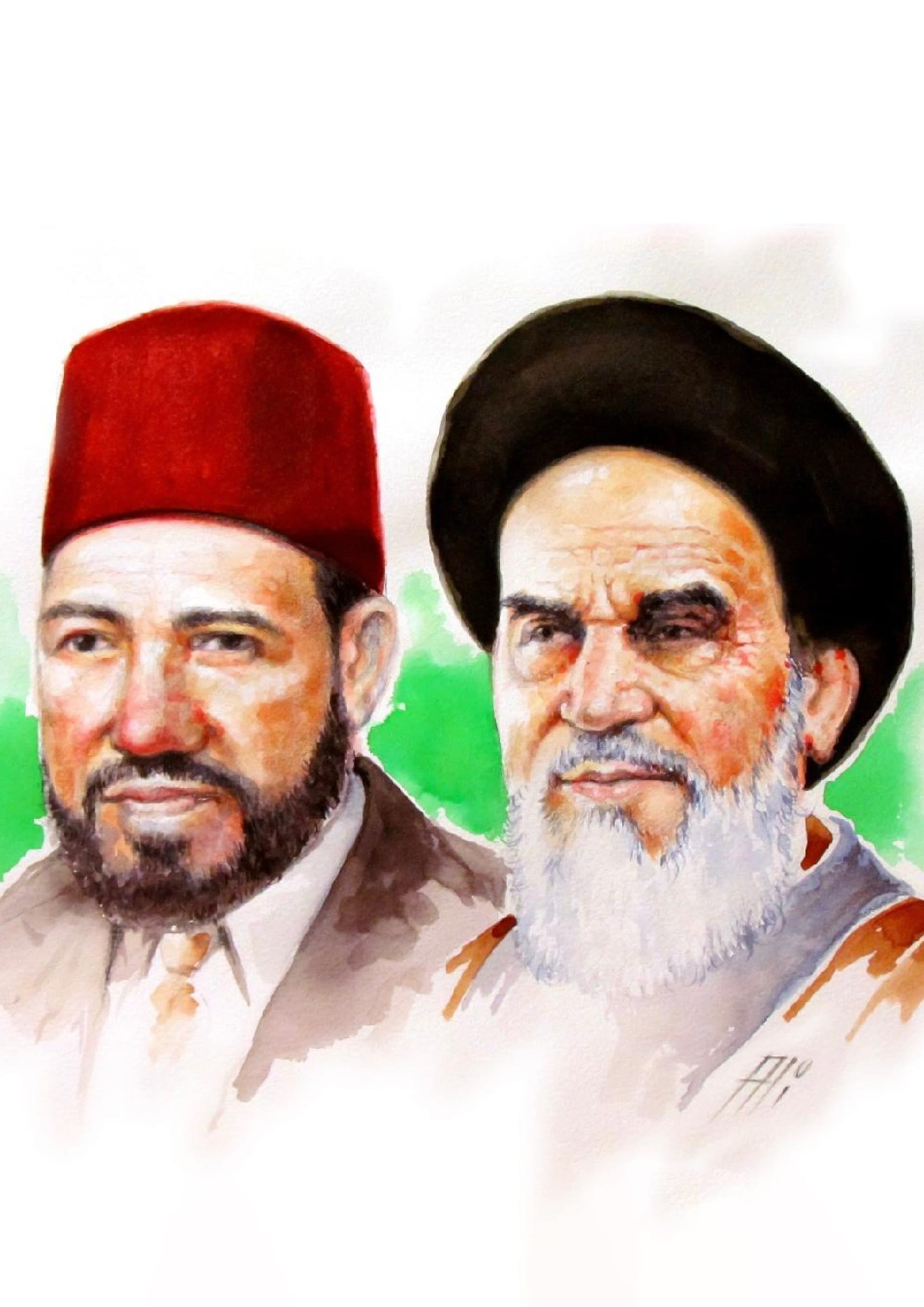

Exporting the revolution

Religious seminaries, including women’s seminaries, also flourished, becoming centres of influence with direct funding from Iran, seeking to export its Islamic revolution. After the civil war ended in 1990, the Islamic Educational Institution—and the schools and institutions under its umbrella—became more prominent. The Islamic Religious Education Association, which established schools and institutions, also pushed to present a religious vision for education.

Within Hezbollah’s educational project, values of dependency were baked in, as evidenced in the content of periodicals, publications, and sermons. In the curricula of schools associated with the Amal Movement and Hezbollah, components of civic culture and national identity are neglected, while affiliation with the sectarian group and its specific religious culture are emphasised. Instead of the national anthem, students in Hezbollah schools instead give the ‘Al-Mahdi’ salute.

Pull Quote: In Hezbollah’s educational project, values of dependency were baked in, as seen in the content of periodicals, publications, and sermons

The activities of schools of the Islamic Educational Foundation, the Islamic Religious Education Association, and the Amal educational institutions are outside the bounds of the freedoms guaranteed by the Lebanese constitution, and outside the values embedded in the general education curricula.

These associations and institutions essentially run in parallel to the Ministry of Education and the Centre for Educational Research and Development, not least in teacher training. Loyalty to a political or religious leader and sectarian culture takes precedence over national identity, coexistence, and commitment to public life.

Loyalty vs tolerance

For Shi’ites seeking to pursue higher education courses, these parties and associations—with their partisan and ideological schools—dominate pre-university education. However, once at university age/level, students have not generally been tempted to study at the same associations’ private universities, choosing instead to get their degrees at more established, non-partisan institutions.

Freedom of education is enshrined in Article 10 of the Lebanese constitution for all sects. The concept of educational freedom does not entail establishing a parallel system to the Lebanese educational system. Likewise, it does not entail replacing a national Lebanese identity with a purely sectarian-religious identity, nor does it involve replacing collective values with those shared by specific sects.

When the schools of Islamic foundations and associations require girls as young as nine years of age to wear the hijab and deny enrolment to non-Shi’ites, there is cause for concern.

The Ministry of Education and the Centre for Educational Research and Development monitor schools’ compliance in relation to the curricula issued by the Council of Ministers. Schools that violate these regulations should have their license withdrawn or suspended until they can demonstrate adherence. Tolerance means accepting differences, both at the community and national levels, and consequently establishing mechanisms that allow for coexistence despite differences.

__

By: Dr Ali Khalife

Prof. Ali Khalife is the founder and director of the Aleph-Ya publishing house, and of Taharror, which campaigns for modern and liberal state in Lebanon. He is a former parliamentary candidate and consultant at the International Centre for Human Sciences, sponsored by UNESCO.