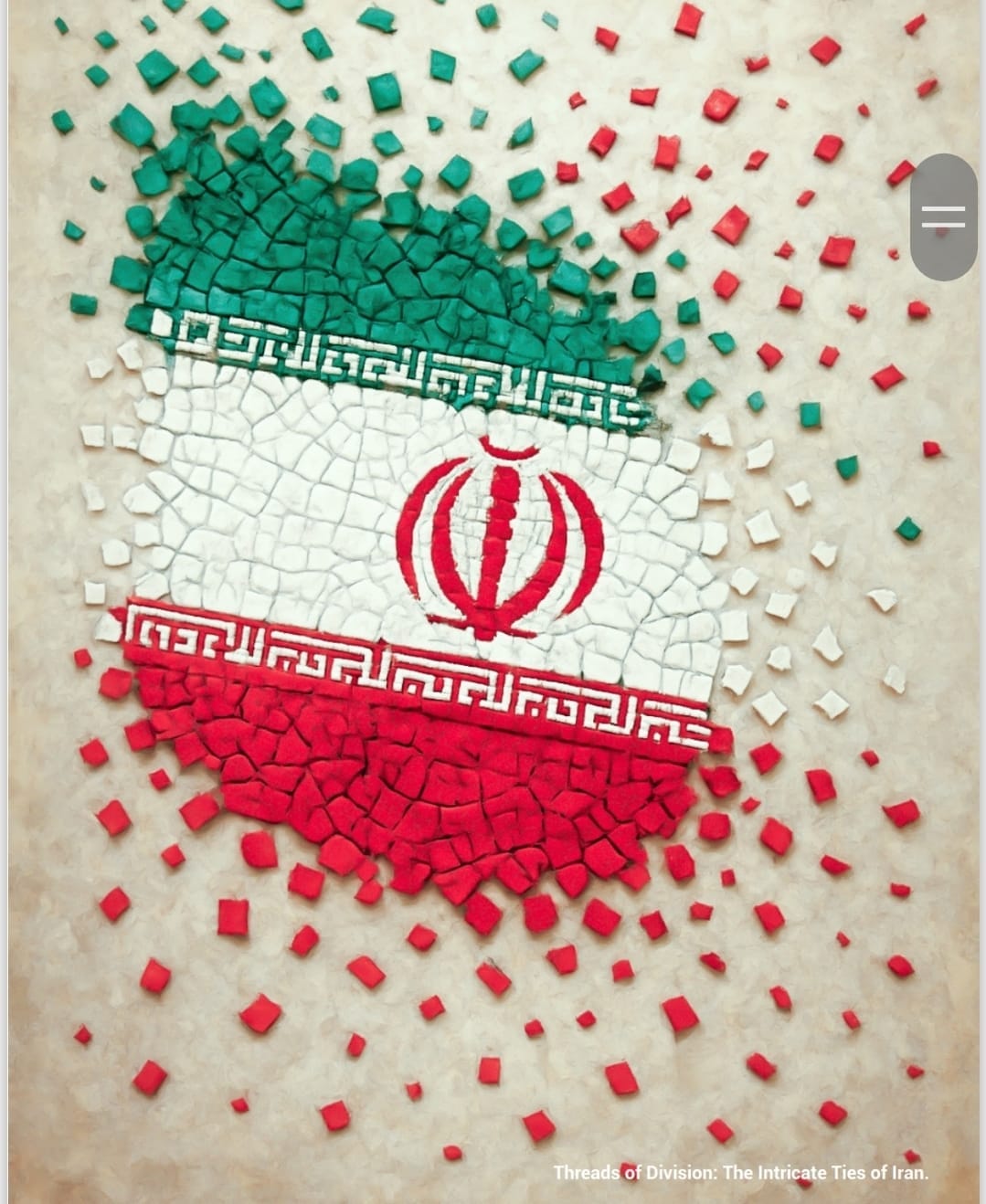

Iran’s disparate and disunited opposition still feared by the regime

The Islamic Republic’s suppression of non-Persian minorities is nothing new—the first Shah had the same idea a century ago. Today, there is both a Persian and non-Persian opposition, albeit all very splintered.

Grasping Iran’s internal dynamics and opposition today requires an understanding of the nation’s post-colonial framework and its wider history.

Iran’s present-day borders were largely drawn around 1871, following the forceful occupation of western Balochistan. Earlier, Iran had reluctantly ceded land in the north to Russia, but by expanding south—through the seizure of land near India and in Balochistan—the regime stabilised an otherwise volatile political landscape.

After a coup by military commander Reza Khan in 1925, Britain—then a colonial power—offered its strategic backing, in part to counter Russian advances. In so doing, it helped forge the modern state by systematically stifling and erasing the distinct national and cultural identities of Iran’s non-Persian populations.

During the preceding Qajar era (1789-1925), Iran had operated as a feudal monarchy, with authority unevenly spread across its vast terrain. Regions like Balochistan, Kurdistan, Ahvaz, Azerbaijan, Lorestan Province, Turkmen Sahra, and Gilan Province functioned autonomously or semi-independently, preserving their unique languages, cultures, and identities. They were a patchwork of regional entities loosely (and often reluctantly) connected to the throne.

Minority suppression

A centralised state emerged after Reza Khan Pahlavi deposed the last Qajar monarch and established the Pahlavi dynasty, Britain playing a crucial role in supporting his efforts to consolidate a powerful central government, which initiated a state-building programme grounded in Persian nationalism. Persian became the official language and non-Persian identities were systematically suppressed.

Most of Iran’s non-Persian communities—which includes the Balochs, Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Azeris, Lurs, and Gilaks—seek greater autonomy, a federal system, or even complete independence. Many have histories of resistance going back long before the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Pull Quote: Before 1925, regions like Balochistan, Kurdistan, Ahvaz, Azerbaijan, Lorestan, Turkmen Sahra, and Gilan functioned autonomously or semi-independently, preserving their unique languages, cultures, and identities

Many continue to their resistance to this day, despite Tehran increasingly intensifying their repression under the guise of “one nation” and “Islamic brotherhood” concepts. In reality, this is a continuation of Pahlavi’s policies of systematically suppressing the linguistic, cultural, and political identities of Iran’s non-Persians.

Splintered opposition

After the revolution of 1979, the opposition became divided. The non-Persian opposition shared common grievances against their discrimination and oppression, but some advocated for federalism, while others fought for self-determination and even secession. The Persian opposition split into three groups: republicans (primarily secular and liberal), royalists (advocating for the restoration of the monarchy), and Mojahedin-e Khalq, or MEK (those with a religious and revolutionary background).

These opposition sub-groups still struggle to unite due to deep ideological contradictions, competition for leadership, and no shared vision, yet many would like to see inter-ethnic cooperation and cross-national coordination. Indeed, there have been some key alliances, and they continue to collaborate.

Opponents of the Islamic Republic (of which there are many) ceaselessly suggest that the state will soon fracture into smaller entities or evolve into a decentralised state, but this trajectory is far from straightforward, in part because Iran is currently in one of the most critical yet fluid and dynamic phases of its modern history. To some, it is teetering. The currency has depreciated sharply and inflation has soared. There is widespread poverty and rising public discontent. Unofficial reports suggest that more than 60% of Iranians now live below the poverty line.

Disgruntled but disunited

A surge in popular protests over recent years tells its own story. The latest ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ movement in particular highlighted the growing tensions within Iranian society. This has led to a crisis of legitimacy, an erosion of popular support for the regime, distrust in national elections (as evidenced by low voter turnout in 2020 and 2024), and frustration over the persistence of Western sanctions which have crippled the economy and led to Iran’s international isolation.

For all the problems, however, the regime’s collapse does not appear to be imminent, in part because the opposition lacks the organisation and strength needed to topple the regime independently. Nevertheless, non-Persians have built networks across the country and gained considerable legitimacy among the younger generation.

Pull Quote: Opponents of the Islamic Republic ceaselessly foretell its fracturing into smaller entities or evolution into a decentralised state, but this trajectory is far from straightforward

Tehran often resorts to negotiations to buy time when confronted with international pressure, as seen with its nuclear programme, but setbacks suffered by Iran’s proxy militias’ in Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, and Iraq have significantly eroded its regional influence, which has left it vulnerable. This ultimately benefits the opposition.

Furthermore, traditional regime tactics to undermine the opposition, from infiltration to assassination, appear to be losing their effectiveness, as a younger generation with access to independent information and means to bypass social media censorship make their own minds up, emboldening activists in exile.

A more moderate face

Masoud Pezeshkian, a Turk from the Azeri region of Iran, was put forward as a presidential candidate in recent elections. Fluent in Kurdish with close ties to non-Persian communities, his selection was a calculated move. Upon winning the presidency in July 2024, he appointed several governors from diverse ethnic groups—including Arabs, Balochs, Kurds, and Turks—to alleviate tensions, restore legitimacy to the elections, and present a more moderate image of Iran to the world.

After Donald Trump’s election a few months later, in November 2024, Tehran re-engaged in negotiations with Washington, hoping that diplomacy would make up for its recent military and security setbacks, while buying crucial time to manoeuvre.

That time is crucial for Iran’s leaders, whose crises are numerous and multi-faceted, involving the economy, regional influence, social protests, the diminishing effectiveness of traditional repression, and a lack of popular legitimacy. Yet the collapse of the regime is contingent upon a strengthened opposition, of which there are only tentative signs.

At any point, a significant international development, or a powerful new social movement, could ignite change in what feels like a politically explosive arena, ultimately leading to the downfall of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The result may even be the disintegration of Iran into smaller, fragmented mini-states. Is that a good or not? It depends on who you ask.

__

By: Habibollah Baloch

*Habibollah Baloch is a former Secretary-General of the Balochistan National Solidarity Party and its current Deputy Secretary-General. He has founded and directed several human rights and civil organisations, including Balochistan Human Rights Campaign and Balochistan Protests Coordination (Sahab).

*